Richard Hogan

When Richard Hogan began producing abstract paintings composed solely of fragile linear strokes in 1978, no one had ever made paintings quite like that before. Who could have thought that just those few spare marks, ticks, and smudges, drawn directly on natural canvas sized with glue, might be enough to make a painting of major ambition?

They seemed like mere sketches for paintings, as if he had lifted his brush away after tracing only some rudimentary outlines. But Hogan's fragile marks were like notations of attention and response that both activated the pictorial space and mysteriously stabilized it. Following a complex range of operations, Hogan laid down lines and then selectively reconsidered them, rubbing them out with solvent and re-striking them with renewed emphasis and sometimes a different color. Over the years, as Hogan's palette blossomed in intensity, blushes of rubbed out color would surround his lines like the glow of a neon tube. These color blushes would eventually thicken and overtake the lines, producing dense", patchwork canvases by the late 1980s.

Throughout, however, the most remarkable characteristic was that each line (or, later, color-form) on these canvases remained somehow separate and distinct. Hogan's procedure is essentially additive: an accumulation of individual elements within a space not unlike the surface of a rock face or cave wall where generations of markers have left their traces, each unrelated to the others except for the holy resonance of the place itself and the impulse to create and leave a token there. As the poet Robert Creeley noted about Hogan's paintings in 1982, "He makes line serve as no direction in or out, but far more as oldtime tally sticks or such markings as one meets with in primordially local places, marking the time and presence of human attention to its amusements, its musing with the edges of where it discovers itself 'on edge,' a place apart."

Creeley understood that Hogan's work contains recognition of human contingency. The separateness of these painterly elements, suspended within an emergent order, reminds us that the things of this world have their singleness and diversity, and that the possibilities for togetherness and connection are not given beforehand, but must be won by attentiveness and candor, and by acknowledgment that separateness is a shared condition.

Hogan's reductive linear vocabulary implies a return to beginnings, to the inscribing of linear marks as the most archaic of art making activities. Yet, despite his deep interest in Paleolithic and Neolithic art, his inquiry into the basic impulse of drawing is not so much a nostalgia for the "primitive" as it is instead a search for a vocabulary that will read as independent or autonomous, and not as "abstracted." Following the Modernist tradition of interrogating the formal bases of his art, his achievement has been to make line a medium of painting.

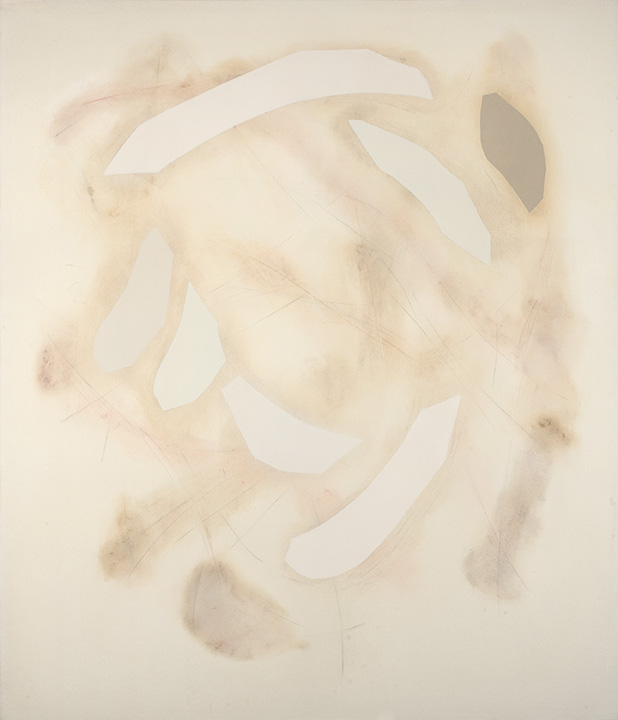

Now, in these new paintings, which resolve themselves out of the mists of many shadowy attempts into a single, hard-won, white line (or pair of lines that act in concert), Hogan has brought a deeper severity to his art. His ageless, bone-white configurations obtain an uncanny quality of liberation and necessity within their refinement. And, as D.H. Lawrence said of Native American dancers moving in lines to muffled drums in Mornings in Mexico: "Everything is very soft, subtle, delicate. There is none of the hardness of representation. They are not representing something, not even playing. It is a soft, subtle being something."

— William Peterson, 2002

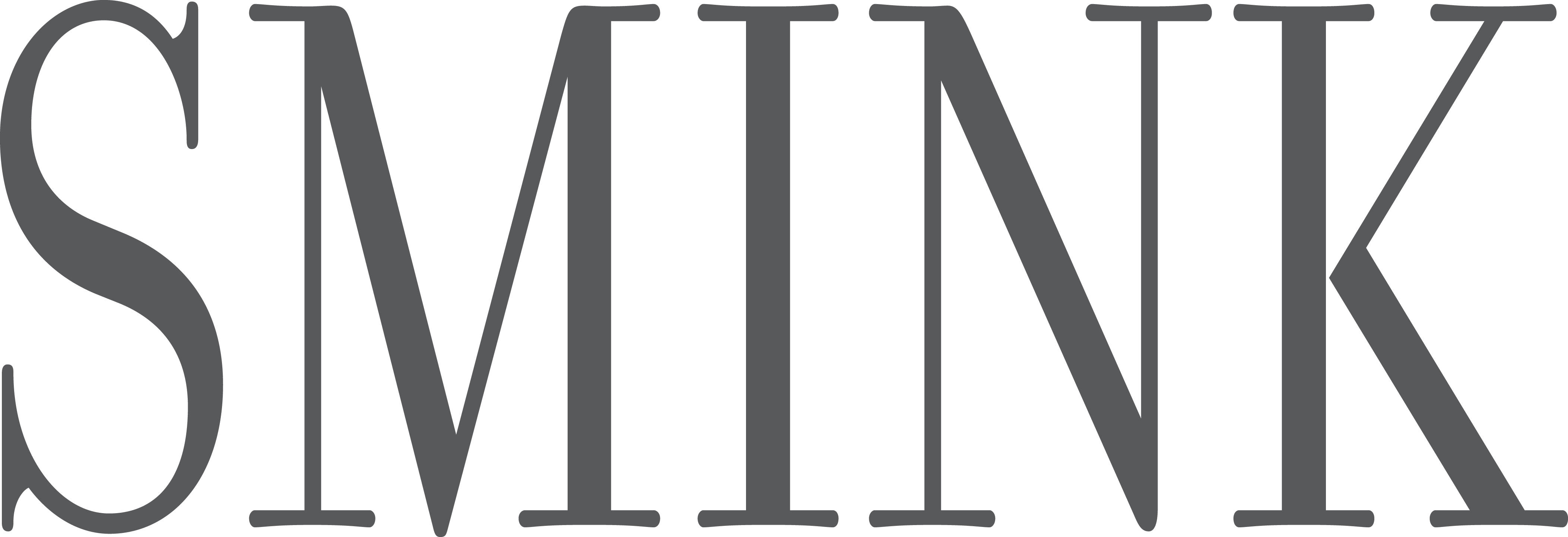

Richard Hogan continues to refine the bare-bones vocabulary of the "White Paintings" that he showed in New York two years ago, extracting his abstract imagery from a field of gestural sketching. In the earlier work he teased a single line from the labyrinth of tentative marks, thickening it with chalky pigment and floating it on the surface as a bold meander. Now he resolves the drawing into an archipelago of broad, island like shapes.

Bleached of their color and flat as flagstones, Hogan's shapes lie on the smudged canvas like artifacts exposed by an archeologist's brush. Behind their unpredictable forms and their mysteriously harmonious configurations is Hogan's abiding interest in Stone Age art, particularly the great megalithic circles of the British Isles. He filled notebooks with lively line drawings improvised from archeological site maps, which formed the basis of both his large canvases and his smaller works on clayboard. In the end, his irregular forms reflect the informality of the rough-hewn and largely unworked stones, the evident but elusive purposefulness of their arrangements, and the random interventions of vandalism, erosion, and time. A family resemblance unites the shapes, but each one has the effect of a separate and anxious apprehension, like elements in late Cezanne.

For Hogan, drawing is the original artistic act, an aboriginal impulse giving birth to art itself. With their stuttered reconsideration, the lines in his earlier works resembled the densely layered marks left on cave walls by generations of Paleolithic tribesmen. But if Hogan's earlier lines implied a contour and a pathway, his new shapes operate as place. Their swirling effect of enclosure replicates the age-old human impulse to define a place of origin, the spiritual center of the world. By means of his painterly process, however, Hogan acknowledges the ineluctable intervention of time into our grandest designs, the inevitability of loss as the price of endurance.

—William Peterson, 2005